The Kamba, just like many African tribes, had simple houses and buildings. Musyi was the basic unit of life across the community. The houses were built on communally owned land, were round and thatched to the ground.

Traditional patterns of family homesteads, existing hitherto, were used throughout the community, with several homesteads of related people forming a clan. The construction of the houses was a community duty, and both genders played a role.

Types of houses and buildings

As pastoralists, the Kamba were constantly on the move to search for water and greener pastures for their livestock. They, therefore, resided in temporary houses which incorporated the main house, granary, cowshed and sometimes a kitchen.

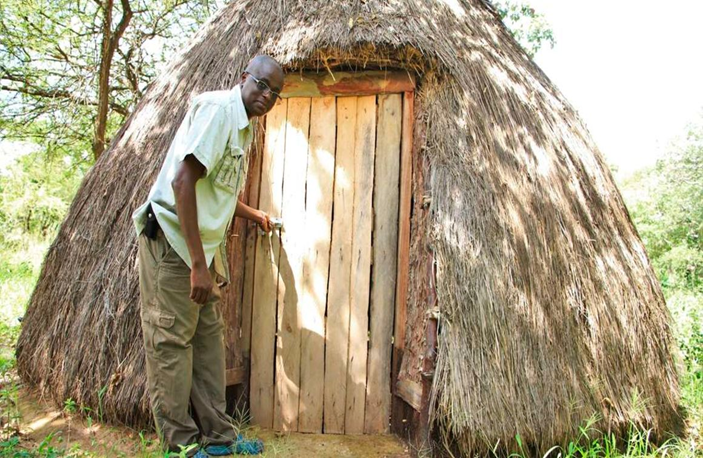

Main house

The main house was a grass-thatched structure called Kisukuu (Isukuu in plural). Both men and women took part in the preparations of raw materials, but only men were allowed to build. Raw materials used included: stones, branches known as Mikonzo and grass.

The stones used were big enough to support the big logs (Muamba) from falling. Young men would collect Mikonza while looking after the livestock, while women would use a tool called Mung'ei to get grass for thatching.

The main house was round-shaped, had only entrances without doors or windows, and the inside had no rooms or subdivisions.

Figure 1: Early Kamba house

Figure 1: Early Kamba house

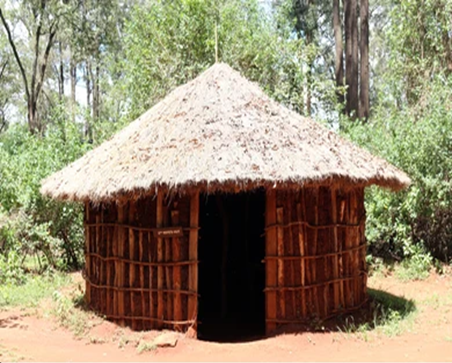

Figure 2: A traditional Kamba house

Figure 2: A traditional Kamba house

Later, people evolved and began to build round grass-thatched mud houses since grass houses were very cold at night. Iron sheets (mabati) also quickly replaced the grass roofs, which were prone to leakage whenever it rained.

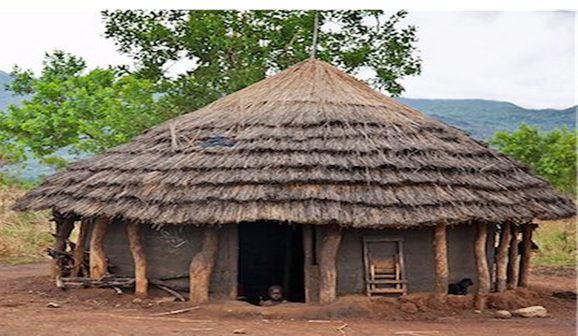

Figure 3: A mud house thatched with grass.

Figure 3: A mud house thatched with grass.

Figure 4: a mud house with supporting logs.

Figure 4: a mud house with supporting logs.

Kitchen

A kitchen, similar to the main house but smaller in size, was built to make cooking safer for women during harsh climates. Usually, only the blocks supporting the cooking pot, known as Mathwiikio, were placed in the open field.

Cowshed

A cowshed was fenced using bushes or thorny acacia plants with an entrance separated by logs with the entryway closed with a special kind of thorny bush. Goats and sheep had a separate shed intertwined up to the top, creating a cone-like structure.

Figure 5: A goat shed

Figure 5: A goat shed

A special structure, a kivanda, was built near the cowshed to store dry maize stalks and grass. It was strong enough to carry as much weight as possible.

Granary

The traditional Kamba granary was round or rectangular, with intertwined branches similar to the goat shed. It was supported by four, six or more logs, referred to as Miamba (Muamba-singular) or chisel-shaped stones firmly planted into the ground.

Stones supported with strong tree trunks laid the foundation of the floor of the granary. In some, soft tree branches were placed on the sides with a secure base to support the heavy weight of the harvest, while in others, sisal trunks were interlocked very well at the edges.

All the roofs were grass-thatched.

Figure 6: A granary

Shape/Appearance

Several families stayed together to provide security to each other.

The compound was not fenced, as it was in the open field, making it easy to locate an enemy from as far as possible.

The cowshed was on the side of the main path into the compound.

Figure 7: A collection of houses in a homestead.

Figure 7: A collection of houses in a homestead.

The head of the family built his house facing the cowshed so that he could easily detect any attack on the livestock.

He also slept near the entrance to protect the rest of the family.

Young men were only allowed to build their houses after the initiation process.

The position of the kitchen was random, as it did not symbolize anything.

The setting up of Mathwiikio was done by an aged married woman as it was taboo for newly married ones to do so.

The granary was built next to the main house to ensure no trespasser could pass by without being noticed. All the entrances of the kitchen, granary, cowshed, and main house almost circularly faced each other for security purposes.

Taboos

There were taboos regulating some activities for men and others for women.

Men were not allowed to enter the kitchen anyhow. Also, a married man could not enter his parent's house anyhow.

Women were not allowed to consume some meat parts like the head, testes and liver as it was for the herders. It was also taboo for girls to cook while stepping on the supporting stones, as that would mean they may never get married.

It was taboo to point anyone with a knife or sword as this signified death.

If an unmarried man died, his body was taken out through a hole drilled into the walls instead of the main entrance. After the burial, ash was sprinkled on his buttocks so no other man resembling him would be born.

Comparison between then and now

House building in Kambaland has drastically changed, thanks to the westernization of the culture. Taboos are not respected, and myths are no longer impactful.

Houses are built depending on the size of the homestead, granaries are built using concrete, and kitchens are incorporated into the main house.

Both genders interact freely all through, and chores are gender-neutral.

Most houses are rectangular, built with bricks and breeze blocks and topped up with corrugated iron roofs.

It has become a free world at last!

Conclusion

The Kamba tribe has a wealth of customs and beliefs which should be taught and documented for future generations.

Our culture is almost diffusing, and most of us do not recall simple traditional beliefs embraced by our forefathers. Sadly, even the traditional Kamba beats and songs are things of the past to the current generation. Children no longer pass through rites of passage as they used to, and the indigenous Kamba meals are not even known.

We need to change and preserve our culture before it perishes.

Special thanks to Benard Kitele for contributing the post and Stephanie for editing this issue.

Remember, it is time to tell our stories. Till next time.

Mike.

Join the Lughayangu Community!