On one afternoon in October 1503, a 50-year-old Italian artist from Florence was approached by his close friend with the request that he make a painting of the wife.

Due to their close relationship, the Italian artist agreed, and for the next four years, the friend’s wife sat before the artist as he drew her.

Instead of gifting them the artwork once he was done, the painter left the artwork in the possession of his assistant, who, upon the painter’s death, sold it to the King of France for a hefty sum.

The painting was kept in the Palace of Fontainebleau for 100 years before the next King transferred it to the Palace of Versailles, where it remained until the French Revolution.

After the French Revolution, it was moved to the Louvre, where it was finally displayed to the public.

It hardly attracted any attention until 21st August 1911, when it was stolen from the Louvre.

This story made the headlines everywhere, with the Louvre even closing for investigations, and a couple of artists being arrested in connection with the story.

It was only two years later that the painting was finally found again in Florence.

The culprit, a Louvre employee known as Vincenzo Peruggio, who was later branded an Italian patriot by his fellow citizens, defended himself by saying that the painting should have been returned to an Italian Museum and displayed there, since that was where it originally belonged.

What do we call that? Repatriation, right? Didn’t know that the Europeans have also been battling the same problems they inflict on us.

As the Swahili wisemen say, ‘Mkuki kwa nguruwe ki tamu, kwa binadamu ki chungu’ (humans enjoy hitting pigs with arrows, but feel pain when they are the ones hit by the arrow).

Africans have, for the longest time, been asking for the artworks taken by the European colonialists to be returned, but these pleas have always fallen on deaf ears.

Today, we’ll focus on an instance where the Italians took away monuments from Africans, ironically, coming after Vincenzo Peruggio’s theatrics.

FYI: The Italian artist in our story was Leonardo da Vinci, and the painting was the Mona Lisa.

Axum – One of the earliest successful civilisations in Africa

The Kingdom of Axum was born around 300 BC in the region that is today northern Ethiopia.

The Kingdom was positioned so strategically, having access to the Red Sea on its right, access to the Mediterranean Sea through Egypt on its north, as well as access to more kingdoms on its south.

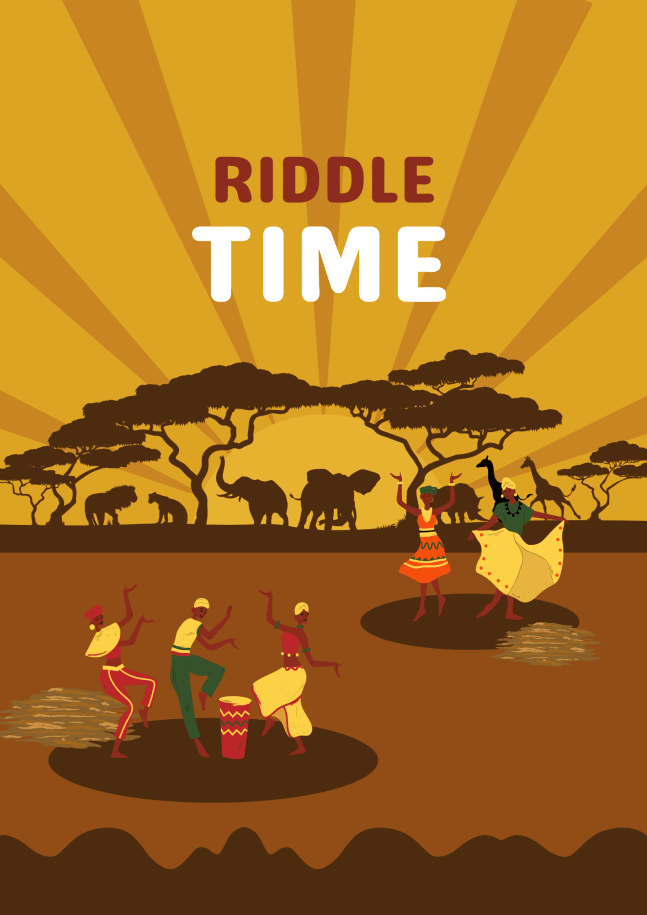

Image 1: The obelisk designs. Credits: Ancient Pages.

Therefore, it had many trade partners, going as far north as the Persian and Roman Empires.

The Aksumites developed a high level of craftsmanship and were the only African culture credited for minting coins, mining precious metals, and producing unique artefacts and pottery.

This, eventually, made them flourish in terms of their power, wealth and culture.

Being a pagan kingdom, they would honour their dead by building obelisks.

These obelisks are tall pillars which serve as ‘markers’ for underground burial chambers.

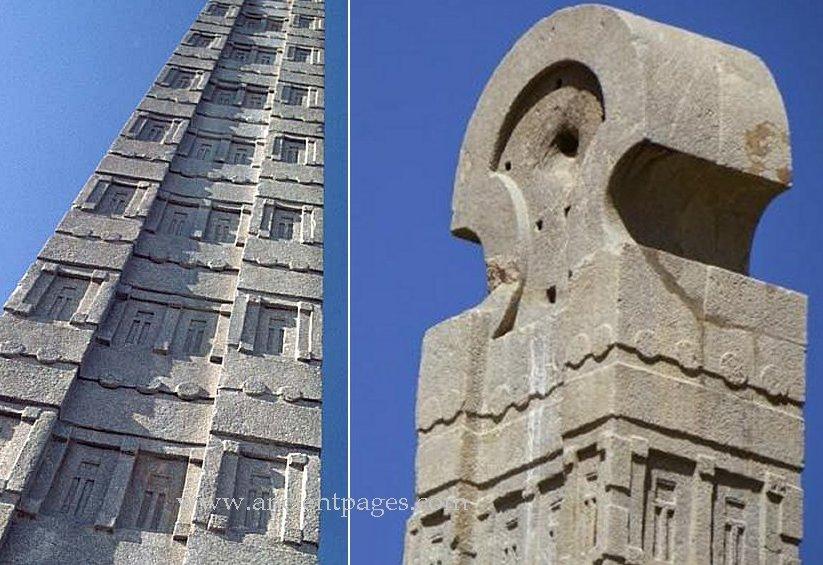

The largest of the obelisks were for royal burial chambers and were decorated with multi-story false windows and false doors, while lesser nobility would have smaller, less decorated ones.

Image 2: Axum's obelisk- a false door. Image credit: jammingglobal.com

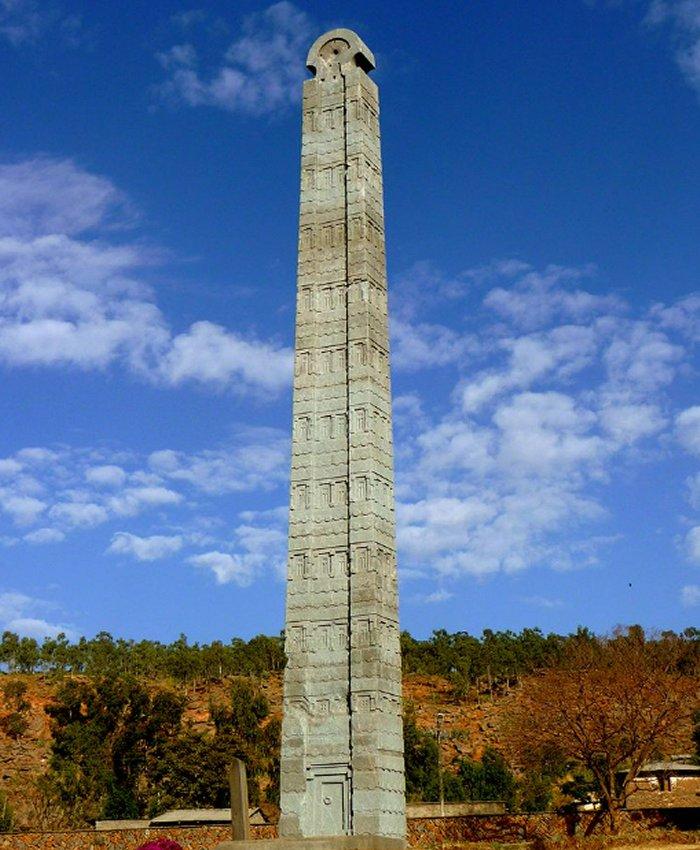

However, in the 4th century, the King Ezana of Axum solidified the Kingdom's conversion to Christianity, and stopped all pagan practices, including the erection of burial obelisks such as the 80-foot Obelisk of Axum.

The Obelisk of Axum was the most phenomenal of all obelisks. It was made of granite and weighed 160 tons. Its ornamentation consisted of two false doors at the monument's base and a window-like decoration on all sides.

Standing only until the 16th century, an earthquake likely toppled the obelisk, and without any importance in a Christian society, it was left in multiple pieces to disintegrate back into sand.

By then, only three major obelisks were erect, with all the others having been demolished or destroyed by earthquakes.

Image 3: The obelisk with how it had fallen. Wikimedia/I, Ondřej Žváček

Enter the Italians

Fast forward to the year 1884, and we get to see the dissection and allocation of African territories amongst the Europeans, during the Berlin Conference.

As Otto von Bismarck said, “Italy arrived late to the banquet with a large appetite and rotten teeth.”

Having faced huge resistance from the Ethiopians at the Battle of Adowa back in 1896, the Italians were prepared the second time, when they came back to fight the Second Italo-Ethiopian War in 1935.

This time, they were successful against the Ethiopians and thus, went on a looting spree, in which the Obelisk of Axum was taken to Italy as war spoil.

The obelisk was cut into three pieces and transported by truck along the tortuous route between Axum and the port of Massawa (Eritrea), taking five trips over a period of two months.

It travelled by the ship, Adwa, arriving in Naples on March 27, 1937.

It was then transported to Rome, where it was restored, reassembled and erected on Porta Capena square in front of the Ministry for Italian Africa.

This square would later become the headquarters of the United Nations' Food and Agriculture Organisation and the Circus Maximus.

The obelisk was officially unveiled on October 28, 1937, to commemorate the fifteenth anniversary of the Italian fascists coming to power through the ‘March on Rome’.

Image 4:Obelisk of Axum in Rome’s Porta Capena Square. Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

The unveiling of the Obelisk of Axum was also a gesture of revenge as per the earlier defeats as well as signifying a new Italian empire.

A bronze statue of the Lion of Judah, the symbol of the Ethiopian monarchy, was taken along with the obelisk and displayed in front of Termini railway station.

Image 5: The statue of the Lion of Judah. Source: Wikipedia

The obelisk did not last four years before the agitation for the return of looted artefacts began almost immediately after the collapse of his forces in East Africa.

This was formalised in the 1947 UN Peace Treaty, which specified the restitution of all stolen objects to Ethiopia within eighteen months. A 1956 bilateral treaty between Ethiopia and Italy further detailed the return of cultural items, notably the Obelisk of Axum and the Lion of Judah.

While the latter was returned in 1967 following the 1961 visit of Emperor Haile Selassie to Italy, little action was taken to return the obelisk for more than 50 years, partly as a consequence of the considerable technical difficulties related to its transportation.

One source suggests that Emperor Haile Selassie, after hearing of these technical difficulties (and of the enormous costs necessary to overcome them), decided to grant the obelisk to the city of Rome, as a gift for the \"renewed friendship\" between Italy and Ethiopia. The Italian Foreign Affairs official even asked that a small notice simply be added to the obelisk declaring ‘A Gift from the Ethiopian People’.

Another controversial arrangement seems to be that Italy were allowed to keep the obelisk in exchange for the construction of a hospital in Addis Ababa (Saint Paul's Hospital) and for the cancellation of debts owed by Ethiopia.

In any case, Colonel Mengistu Haile Mariam, who overthrew Emperor Haile Selassie’s regime during a Marxist uprising, as well as the new Ethiopian government that came after him, asked for the return of the obelisk, finding a positive answer from the then-president of the Italian republic Oscar Luigi Scalfaro, in April 1997.

However, due to technical difficulties, the process did not start until six years later.

The first steps in dismantling the structure were taken in November 2003. The intent was to ship the obelisk back to Ethiopia in March 2004, but the repatriation project encountered a series of obstacles:

- The runway at Axum Airport was considered too short for a cargo plane carrying even a third of what the obelisk had been cut to.

- On the other hand, the roads and bridges between Addis Ababa and Axum were thought not to be up to the standard of road transport.

- Access through the nearby Eritrean port of Massawa, which was how the obelisk originally left Africa, was impossible due to the strained state of relations between Eritrea and Ethiopia.

Although the obligation for Italy to cover expenses related to the repatriation of Ethiopia’s stolen heritage dates from the 1947 Peace Treaty, it was not until a new protocol was signed in November 2004 that the process truly got underway. Axum’s airport was duly expanded to receive the Antonov cargo plane that would transport the structure in three separate sections, reportedly the largest air freight in history, and the transfer of the structure was completed in April 2005.

The operation cost Italy $7.7 million (they might need to ask Mussolini whether it was worth taking it in the first place).

Also included in the restitution cost was eventual reassembly and restoration under the supervision of UNESCO, notably the insertion of plastic-ish reinforcement bars (instead of steel) to avoid the repetition of a lightning strike that had earlier damaged the obelisk’s summit.

The entire operation was concluded in preparation for a ceremony in September 2008 that marked the closure of Ethiopian millennium celebrations.

The obelisk remained in storage while Ethiopia decided how to reconstruct it without disturbing other ancient treasures still in the area. By March 2007, the foundation had been poured for the re-erection of the obelisk, structurally consolidated on this occasion.

Reassembly began in June 2008, with a team chosen by UNESCO and led by Giorgio Croci, and the monument was re-erected in its original home and unveiled on 4 September 2008.

Image 6: Unveiling the Obelisk after repatriation. Image courtesy UNESCO

“Underground chambers and arcades have been found in the vicinity of the original location of the obelisk,” said Elizabeth Wangari of UNESCO’s World Heritage Centre and Jim Williams, of the agency’s Culture Sector, who took part in the repatriation mission.

“Geo-radar and electrotomographic prospection, the most advanced technologies for underground observation, revealed the existence of several vast funerary chambers under the site’s parking ground which was built in 1963.”

Image 7: The Rome obelisk (also known as the Aksum Obelisk) in Aksum (Tigray Region, Ethiopia). Image credit: Ondrej Zvace

So, after decades in Rome, the Aksum Obelisk finally stands tall again in its rightful home. More than just a stone monument, its return is a powerful symbol of cultural reclamation and a victory in the ongoing global conversation about the restitution of looted artefacts. While the obelisk's journey home is complete, the call for other colonial powers to return the treasures they took from Africa continues. The Aksum Obelisk's story is a reminder that sometimes, even the longest journeys home are possible.

Join the Lughayangu Community!