In high school biology, we learned about something called a ‘food chain’, which means a linear sequence of organisms where nutrients and energy are transferred from one organism to another.

Think about how the sun would produce energy. This energy would then be absorbed by grass through photosynthesis. While grazing in the wild, a deer would come and eat this grass. Then a lion, in its hunt, would come and eat up the deer. Eventually, the lion would die and a vulture would eat its decomposing body.

Figure 1: Examples of food chains. Source: Teachoo

That was a food chain, complete with the source of energy (sun), the producer (grass), the primary consumer (deer), the secondary consumer (lion), and the tertiary consumer (vulture). And that is how a proper ecosystem is. Any attempts at removing or adding another species to the food chain end up disrupting the balance of the chain and thus the ecosystem entirely.

An example of an organism being removed from the food chain was in 1950, when the Chinese, under Mao Zedong, decided to kill all sparrows because they feared they were feeding on all the rice they were harvesting.

Upon killing the sparrows, the number of locusts in the land sharply increased, and all these locusts fed on the harvest, leading to a famine in China, where as many as 15 million people died. To recover, they had to import 250,000 sparrows from the Soviet Union to restore the balance of the food chain.

Figure 2: Chinese Sparrow Campaign. Source: The World of Chinese

That was an instance when a predator was taken out of the food chain. But today, we’ll look at an instance when a predator has been introduced into the food chain.

The predator of Lake Victoria

At the same time when Mao Zedong was killing all the sparrows in China, the British colonial govt in Uganda was introducing the Nile Perch (mbuta) to Lake Victoria with the purpose of having fish for sport as well as for export to European markets.

You see, the Nile Perch is a species of fish that could grow to be as huge as 130kg, therefore, the colonial officers saw the potential of having this fish for export, and so, they planned to rear it. What they didn't consider, a decision that came to be fatal, is how much of a predator it was.

Figure 3: Nile Perch. Source: Animalia Life Club

Lake Victoria, as any natural environment, had its own food chain that had stabilized over the years. The Nile Perch had never gotten here (despite the River Nile being connected to the lake) because the Kabalega Falls and Owen Falls were impassable by fish.

It all started in 1950 when the colonial officials wanted to develop fisheries among communities which are further away from the lake, so they decided to introduce them to ponds around the lake.

In 1954, the same colonial officers of the Fisheries Department decided to secretly introduce fingerlings (of the Nile Perch) to the lake. This came despite earlier warnings from biologists and FAO scientists that thou shalt not introduce a predator to Lake Victoria. In 1959, they did the same. And so did they in 1962 and in 1963.

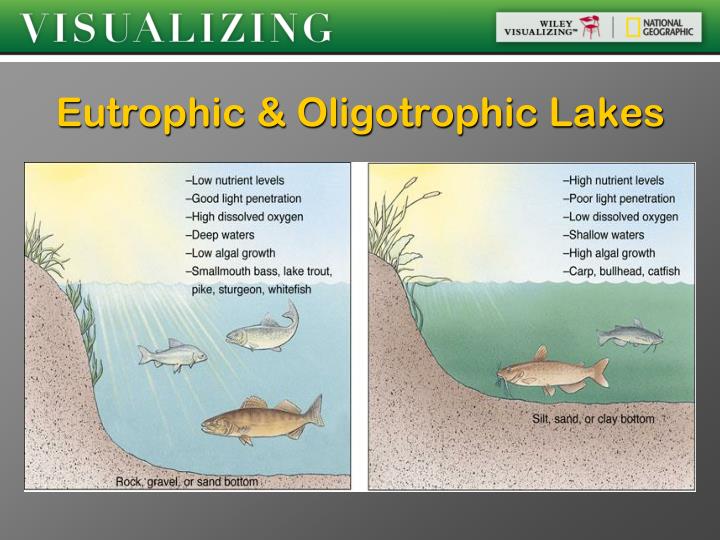

For a while, nothing changed, until 1980, when scientists noted that the lake had changed from an oligotrophic state (clear water with no sediments) to a eutrophic state (polluted water with dense plant population).

Figure 4: Oligotrophic Lake vs eutrophic lake. Source: Slideserve

Upon further investigation, they realized that the biomass of the Nile Perch had exceeded that of all the other species in the lake, whose numbers had significantly gone down.

Some had even become extinct. True to word, in 1988, when the World Conservation Union listed 596 freshwater fish that were in danger of extinction, almost half of them were in Lake Victoria.

The Nile Perch had literally colonized the lake as those who introduced them had colonized the land around it.

As recently as 2008, it was reported that having exhausted all the other species, the Nile Perch had started feeding on its young ones.

This year marks exactly 70 years since the error was made, and it seems like scientists have been unable to solve it. Should they hunt them all down to extinction? Or should they hope that they run out of food and die?

Special Mentions

✅ The Sour Aftertaste of an Invasive, Sugary Shrub

✅ Water Hyacinth in Africa and the Middle East

Join the Lughayangu Community!