The past week has been a heated one in Kenya. Streets have been thronged like never before. Not even the election campaigns saw these many people out at once. The streets of the Nairobi CBD were full from one end to the other. But it wasn’t only Nairobi, but also Eldoret, Mombasa, Kisumu, Kericho, Nyeri, Kisii etc. In short, 35 out of the 47 counties were up in arms. Whatever was happening in the other 12 was up to question, but that’s a question for another day. So, why were all these people out in the streets?

Well, the government of Kenya intended to pass a bill known as the Finance Bill 2024, which would introduce very punitive tax measures, including:

- 16% VAT on bread

- 2.5% Motor Vehicle tax

- VAT on cancer treatment machines

- Eco-levy of ksh 150 per kilo

Kenyans submitted their views during the public participation period, but despite the huge opposition to the bill, the Members of Parliament still voted in support of the bill. Therefore, Kenyans, particularly, the youth, were left with no option but to go on the streets and fight for their rights. For four days, then, they marched, with the aim being to Occupy Parliament and State House so that they could have a few words with their representatives.

However, as expected for any African police force, they opened fire on the crowd and killed a couple of people, with the first martyr being Rex Kanyike Masai (RIP). The matter escalated with a raid in Parliament that saw the MPs run away and the deployment of KDF to quell the tension. In the end, the President called a presser, withdrawing the Finance Bill 2024 entirely.

Whether that is legal or not constitutionally, it was a sign of imminent victory among the demonstrators. And, seeing the youths fight for their country reminded me of a similar event in the past: The June 16 Soweto Youth Uprising.

Let me take you on a short tour of South African history.

The year was 1953. Dr. Hendrik F. Verwoerd, the head of the Department of Native Affairs, had just introduced the Bantu Education Act. This Act would ensure that there was segregation and discrimination against Blacks in the country. In a speech, Dr Verwoerd said, “Blacks must be taught from an early age that equality with Europeans is not for them.

This also led to a crippling of studies in schools for the Blacks, due to a dire shortage of resources, classrooms and teachers. The government was spending far more on White education than it was on Black education. As time went on, more students were dropping out.

In 1976, the Deputy Minister of the Bantu Education Department, Andries Treurnicht, sent instructions to School Boards, inspectors and principals, that Afrikaans should be put on an equal level with English as a medium of instruction in all schools. This decree drew immediate negative reactions from all corners of the community. The teachers complained that they were not fluent in Afrikaans. The students, on the other hand, were not comfortable learning the language of their oppressor. Additionally, a change of language of instruction forced the students to focus on understanding the language instead of the subject material. That made critical analysis of the content difficult and thus discouraged critical thinking.

By 30th April 1976, the school kids had already become rebellious because of it. Those in Orlando West Junior School even declined to go to school, and they were later joined by others in Soweto. One student from Morris Isaacson High School called Teboho Mashinini, proposed a meeting on the 13th of June 1976 to discuss what should be done. Together, they organized a mass rally on the 16th of June.

On the morning of 16th June, around 15,000 black students walked from their various schools to Orlando Stadium for a rally to protest. They were led by the one and only Teboho Mashinini. A few kilometres after they had taken off, they realized that the police had installed barriers along their route. They diverted to another route and started walking in that direction too, with placards in hand.

The police, seeing that they’ve been bypassed, decided to send their dog to the protesters, who simply responded by killing it. The police, angered by this, decided to open fire on the children, shooting at them.

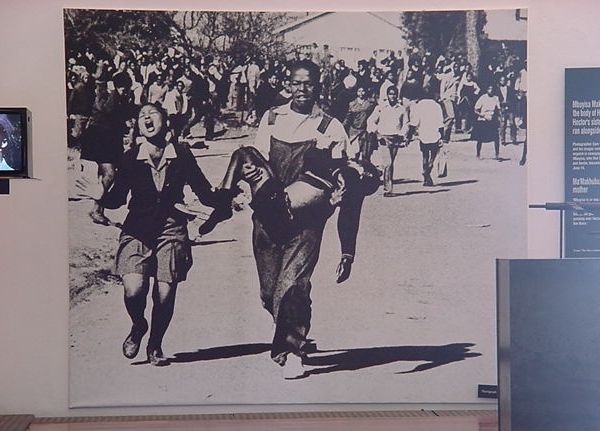

The kid, who’s remembered the most as the hero, was one Hector Pieterson. 12 years old, he is remembered most because of the iconic photo that was taken of him, right after he had been shot. At this time, he was being carried away by Mbuyisa Makhubo, with Pieterson’s sister, Antoinette Pieterson, on the side. This photo was taken by Sam Nzima, and it ended up being the symbol of the Soweto Uprising. Violence escalated, and more kids were shot at, including 15-year-old Hastings Ndlovu.

Figure 1: Nzima’s famous picture hangs at the Hector Pieterson Museum in Soweto.

In the end, 700 kids died, even though the government placed this number as 176. The number of those injured stood at over 1,000 people.

This event saw a huge change in South Africa. Black resistance grew, as they realized the strength they had against the white man. The liberation movements that existed gained new momentum, as a huge number of recruits joined.

The next day, even white students in the university joined in the protests, as well as black workers, who had downed their tools. The international community even boycotted South Africa’s products, leading to economic instability.

In the end, the kids had their way, and the decree to forcefully learn Afrikaans was repealed. As for South African apartheid, it was never the same.

Maybe, just maybe, the Kenyan youth might have an equal chance at success. Let’s hope and see.

Special thanks to Keith Angana for the article.

Join the Lughayangu Community!